PERMANENT EXHIBITION

Imagined rooms [II]

Reconstructing the history of a house invites us to move through its spaces and find out who lived in it, but to do so, also, by going to the different moments and ways in which all this existed. The history is not unique or exact, the moments are always multiple and variable. For this reason, the interpretation of heritage supposes the development of a creative process that must activate and combine, in a balanced way, knowledge and emotions.

A room not only refers to the space in it and it’s purpose, but also to the period of time that someone stays in it. And imagining has both the free range of inventiveness and the ability to represent with images. Starting and playing with these dualities, an interpretive exercise is proposed here that seeks to activate several extremes: on the one hand, the reference to the events in these parts of the house, what were their uses and occupants; on the other, the incorporation of a diverse imaginary, a priori unconnected with it, but proposed as a possible dialogue with the history of art; and, consequently, a tour through a selection of works from the LM Collection, grouped under the theme or fundamental ideas suggested by each area, and which involves a non-chronological approach to the Canarian art scene of recent times.

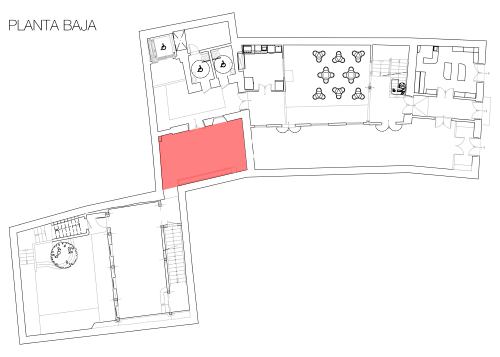

The stable (metaphors and allegories)

Yesterday, a place for the beasts; today, an entrance to a museum. Only an ancient dornajo remains from that time, a huge hollowed-out trunk that years ago served as a feeding trough for animals, but which over time became a magnificent object of surprising beauty. Immersed in the city, there is no longer room for stables or horses. Everything has its moment. The uses, the looks, the needs, they all change. Like a complex allegory, those beings and objects, previously basic and functional, now become illusions of themselves, protagonists and representations of new ideas, but perhaps they actually speak of us, of our fears and desires, of freedom or memory, death and survival, or irony and humor.

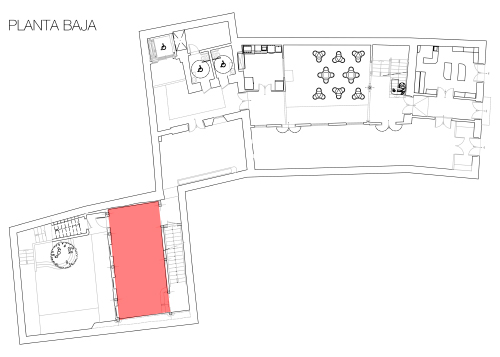

The garden (nature and artifice)

Cultivating nature –be it the orchard or the garden that has always existed here– implies human intervention, activating an artificial arrangement in what we admire as spontaneous. In fact, the very idea of nature seems like an artifice, since it is our gaze that recognizes and measures it. Representing the garden further complicates the equation, since it would become a simulacrum of a simulacrum.

However, and nevertheless, it is not a question of resemblance; the question is not necessarily how similar the painted rose is to the full-grown flower, but precisely how it has been cultivated and through what glass we see it.

The sky (air and cosmos)

Over the garden, the immense breath of the trade wind shakes the branches of its plum tree, twisting the iron trunk in one more turn. In another time in this space there was only light and air, alternating with the imposing darkness of the cosmos, which crushes the earth every night. It is probable that, despite its ethereal, formless and immaterial condition, the sky is one of the most frequent motifs in the history of painting, since it appears usually over the sea, cities or landscapes. However always repeated, it is never the same. The infinite variation of tones and lines of light, reflected in the wavy back of the clouds and in the edges of the dusk, generate a continuously changing portrait, as static for the instantaneous gaze as fickle in the face of the passage of time.

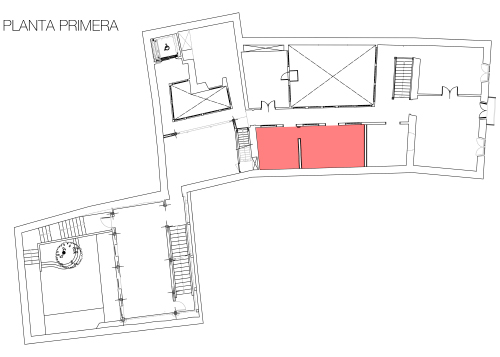

The kitchen (still life)

The most essential and warmest place in every home, hearth itself. The kitchen is linked to cultural processes in which the dialogue and encounter between the traditional and experimentation, acquire special significance. In a similar way, the still life in art, was usually nourished, above all, by the elements and belongings typical of this space (succulent delicacies, tableware and crockery, or perfectly transparent glassware) was considered a minor gender compared to others such as the historical or the religious, although it always highlighted, in a prominent way, the complex challenge that implies the representation of reality, as well as the suggestive potential of the symbolic and the allegory reflected in its objects. But, also, the surprising capacity of art to disrupt or transfigure the image of the recognizable.

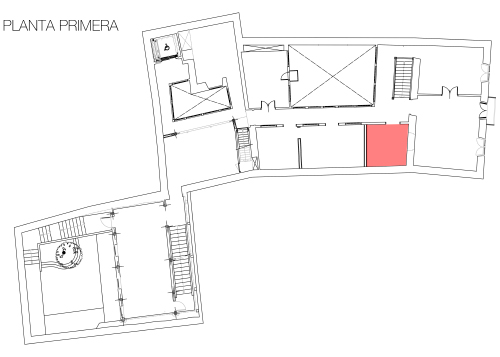

The dining room (custom and exchange)

The transformation processes that art can achieve have much to do with the usual processes of food and digestion, seen from a broad and social perspective. But, in addition, in the dining room there are issues that go far beyond mere eating; sociability, the act of sharing a table eating and drinking, is associated with the transmission and enjoyment of cultural values and identities. At the table, as on the canvas, we rediscover inherited and repeated traditions, distilled over time, and it is also at the table —and much more so on the canvas—, in that gesture of sharing recipes and enjoying all its sensory notes, where we frequently seek the novelty of the other, even the strange way, which we often end up making our own.

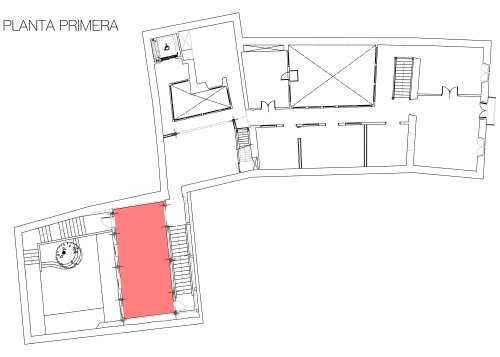

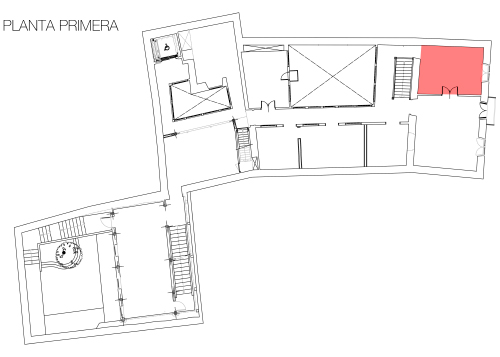

The bedrooms (portraits and bodies)

There is news of who some of the people who inhabited this property were, as well as scattered data on what their history was. But the list is only partial, and the portrait of the acquaintances is incomplete. Consequently, the house’s background is also incomplete, which also has not stopped undergoing transformations and being adapted to new uses and needs over more than two centuries. Portraying time, forces us to choose instants and also, to interpret the before and after. Imagining those who lived in these spaces, invites us to recreate their faces and bodies, the hardness of their lights and shadows, or the searches and destinations they longed for, tracing possible interior landscapes, built on the fine line that often runs between desire and memory.

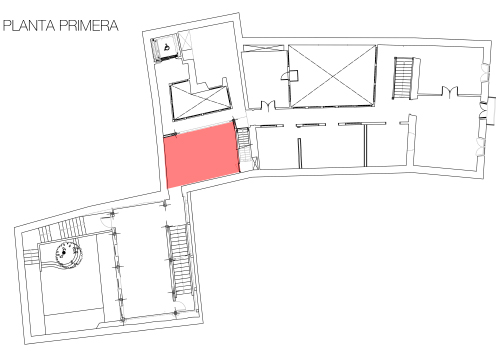

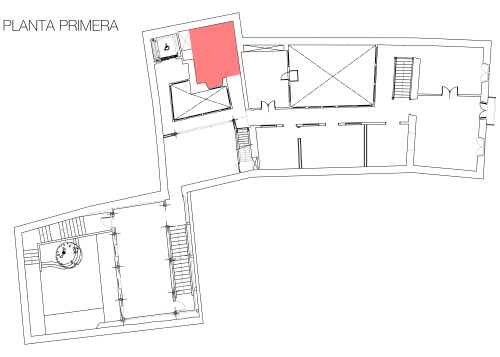

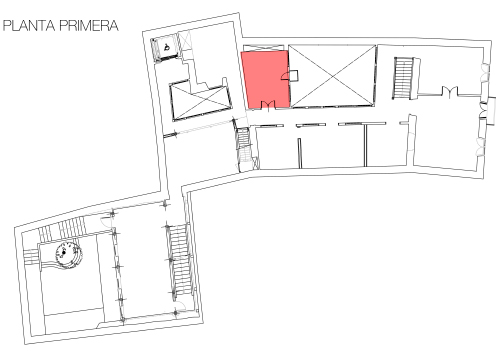

The oratory (iconography of the mystical and the religious)

Hidden behind a crude hurdle roof for decades, the proportions of the coffered ceiling of Mudejar tradition and the perfect geometry of the decoration that finishes off its almizate, seem to indicate the differentiated use that this space must have had in another era. Presiding over the upper part of the main staircase of the house, it would serve as an antechamber to the main hall, but perhaps it was at some point a small oratory, in which the visible reality of the symbolic elements was completed by devotion and faith in the invisible. Under this contradictory duality, all power is granted to the immaterial, although resorting to the iconographic capacity of bodies and objects as a vehicle for dialogue, linked to ritual and tradition. However, the tradition also changes inexorably with the passage of time and varies depending on the circumstances or according to the different perspective of those who carry it out and transmit it.

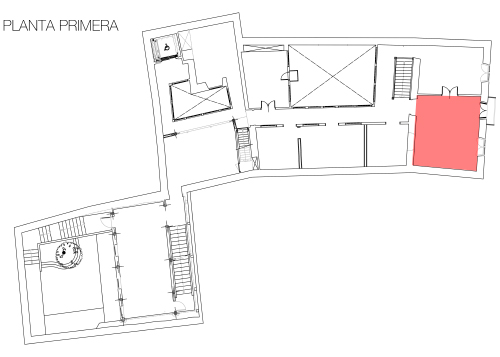

The living room (myth and landscape)

The main room of the house was used for guest receptions and feasts. An 1858 inventory lists silver candle holders, mahogany and marble tables or mirrors with gold trim, reminders of class splendor. Half a century later, in 1903, the façade of the building was modified, hiding the traditional simplicity of the domestic –wall, roof tile and wood–, behind an elegant eclectic frontispiece, very much in the European fashion, in which the classical arrangement is blended with brief modernist glimpses. A glimpse of bourgeois splendor that was also reflected in the Canary Islands’ paintings, especially landscape painting, which moved during the 19th century between classicism and the romantic, between the real and the idyllic, later opening the way to the memory of the Fortunate Isles myth and regionalist sentiment, then confronted by the avant-garde with a look of light and synthesis. By then, hosts and guests had already changed homes in its landscapes.

The dream

At the foot of the hall, in this room there were kept paintings and sculptures of saints, virgins and landscapes. Also, a damask-lined mahogany love seat and pillow. On its memories, the basting of time awakens us in a different room, inhabited by improbable beings and forms. Impossible then, surreal now. A strange island within a story imagined, fantasy of a distant dream that finally arrives. A half-open mythical chest with a woman’s name.

The gallery (light and structure)

The backyards have served in Canarian domestic constructions as key elements, just as structure and light are fundamental for architecture. Also, to sculpt or paint. Beyond the mere illuminated support, light and structure define and articulate spaces and volumes, surfaces and lines. In this complementary disposition, corridors and galleries, which serve as a passageway between rooms or enclose the backyards between their windows, are prolonged as interlinked elements, which allow effective communication between rooms, although other times they are a dark labyrinth in which everything seems to get lost, even the most radiant lights in sight.

.